Blogs

Skelling Michael History

Skellig Michael History: Monks, Vikings & Star Wars

The Skellig Michael history is written in stone, storms, and centuries of human grit. Out here, 12 km off Ireland’s Kerry coast, a jagged island rises straight from the Atlantic. First, it was only seabirds and sandstone, laid down 360 million years ago. Then came the monks.

In this article, we’ll move step by step through Skellig’s past:

- 6th–8th centuries – the daring monks of St. Fionán.

- 9th century – Viking raids that tested their faith.

- Medieval centuries – life, death, and pilgrimage.

- 19th century – the age of lighthouses and sailors.

- Modern times – UNESCO, Star Wars, and fame.

It’s a timeline of solitude, faith, and survival. Read on, and see how Skellig Michael has carried its story from prayer to pop culture.

6th–8th Century: The Beginnings

Long before monks set foot on Skellig Michael, the island itself was already ancient beyond imagination. Its bones are Devonian sandstone, laid down 360 million years ago when Ireland sat south of the equator, in a hot, semi-arid land.

Rivers filled the Munster Basin with sediments that hardened into rock, later folded and fractured by mountain-building. Those forces shaped the island’s twin peaks and the saddle between them, leaving diamond-shaped cracks and brittle ridges that storms have battered ever since. For millions of years, Skellig Michael was nothing more than a storm-lashed outpost of stone and seabirds.

But history begins here in the 6th–8th centuries, when men climbed its sheer cliffs and called it holy ground. Tradition credits St. Fionán with founding the monastery, part of the Celtic Church that prized hardship and exile as paths to God.

These monks embraced peregrinatio pro Dei amore – “pilgrimage for the love of God.” For them, to settle on a rock 12 km offshore was no accident: it was devotion in its most extreme form. Skellig Michael became not just a mountain of stone, but a monastery in the clouds, a place where solitude, faith, and survival intertwined.

Today, visitors can still follow the same path of devotion by climbing the south steps on the Skellig Michael Landing Adventure.

9th Century: Viking Raids

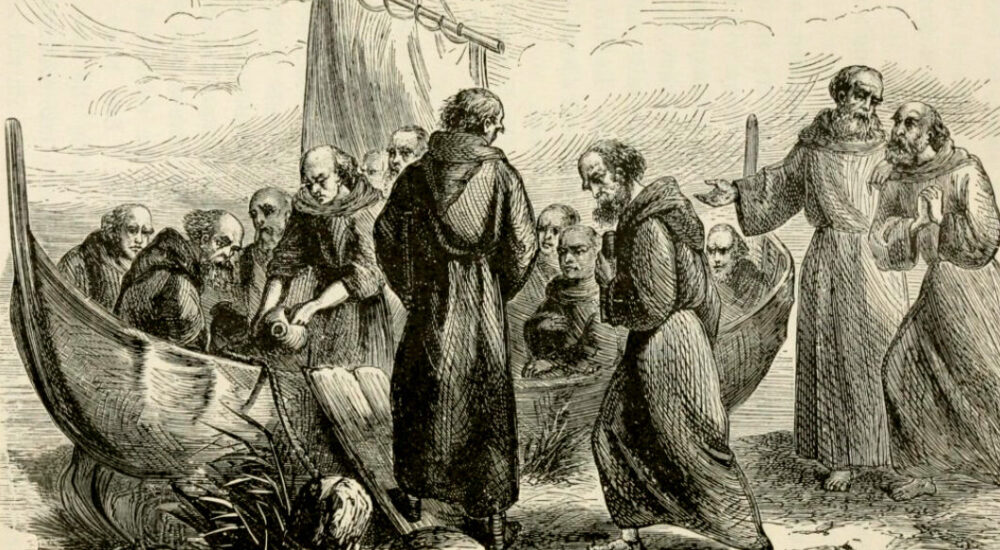

If solitude was what the monks of Skellig Michael sought, the 9th century shattered it with sails on the horizon. In 821, Vikings plundered the island. The abbot, Étgal, was seized and carried into captivity, where he died three years later of hunger in 824. For the monks, it was terror brought by sea – their enemies arrived in the same way they themselves had once come: by boat, swift and unstoppable.

The island’s three flights of steps, carved to give the monks landing options in different seas, became a curse in this age of raids. Vikings could approach from several sides at once, overwhelming the small community. Perhaps that is why the monks built their remote hermitage on the South Peak – a near-impossible refuge where they might escape when the Northmen came.

Still, the monastery endured. By 860, the abbey was reedified – rebuilt after the violence. Faith returned even where fire and fear had tried to root it out. It’s a reminder that this remote rock, reached today by The Ultimate Skellig Coast Tour, was once a fortress of faith under constant threat.

And then comes the ironic local legend. It’s said that in 993, Viking Olaf Trygvasson, who would one day be king of Norway, arrived at Skellig Michael intent on a raid. Instead, the tale goes, a hermit baptised him into Christianity. The man’s offspring, Olaf II, became known as a patron saint of Norway!

10th–11th Century: Life Continues on the Rock

Despite Viking raids and the constant battle against sea and storm, life on Skellig Michael did not end. The Irish annals record the passing of abbots across these centuries, each name a faint echo of a community that endured:

- 882: Abbot Flannmac Cellach died.

- 950: Blaithmhac of Skellig died.

- 1044: Aed Scelic, remembered as a “noble priest,” passed away.

Their deaths remind us that this was no mythic outpost but a lived monastery, with generations of monks climbing the same steps, tending the same terraces, and praying in the same small huts.

The settlement itself continued to grow and evolve. The monks maintained their drystone construction – beehive huts, oratories, cisterns, and terraces – built without mortar, yet resilient enough to withstand centuries of gales. These structures still cling to the rock today, proof that devotion and skill could make permanence out of such fragile exile.

11th–12th Century: Change and Expansion

By the 11th century, the monastery on Skellig Michael began to change. A mortared church was built – sturdier, more permanent than the earlier drystone oratories and cells. It marked both an architectural and a spiritual shift, showing the community’s continued importance in Ireland’s religious landscape.

In the 12th century, the island’s role expanded into a wider network of devotion. A priory of Augustinian canons was founded at Ballinskelligs Abbey on the mainland, closely linked to Skellig Michael. The canons likely used the island seasonally, keeping its monastic life alive while also drawing pilgrims. Offerings from those pilgrims sustained both Skellig Michael and the new mainland abbey, tying the storm-lashed outpost to a broader rhythm of faith.

Late 12th Century: Abandonment of Daily Monastic Life

By the late 1100s, the monks withdrew from permanent life on Skellig. Gerald of Wales wrote that the hazardous position of the rock forced their retreat. From then on, the island was used by hermits and pilgrims rather than a permanent community.

Medieval to Early Modern Period: Pilgrimage and Memory

Even after the monks left in the 12th century, Skellig Michael did not fall silent. The island lived on as a site of pilgrimage, its steep 600 steps and stone huts transformed into a path of penance for the faithful. To reach the monastery was to endure hardship – rough seas, sheer climbs, and the exposure of the Atlantic – all embraced as acts of devotion.

Pilgrimage to Skellig continued through the medieval period and well into the 18th century, when it was still spoken of as a place of prayer and trial. By then, the chants of monks had faded, but their memory lingered in the worn steps, the weathered crosses, and the enduring belief that this storm-lashed rock was closer to God than the mainland ever could be.

19th Century: Lighthouses and Secular Use

By the 1820s, Skellig Michael’s story turned from prayer to navigation. The Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin – later the Commissioners of Irish Lights – took control of the island in 1820 and set about making the Atlantic safer for sailors. Two lighthouses were built on the island’s western side, staring out at the endless sea, and they commenced operation in 1826. To support them, workers blasted and carved a road and pier, reshaping parts of the ancient landscape. The upper lighthouse, perched high on the rock, was later taken out of use in the late 19th century and today survives only as ruins.

For decades, lighthouse keepers and their families lived and worked here in extraordinary isolation, raising children, keeping supplies, and maintaining the lights in all weathers, their lives shaped by the sea, the weather and the long Atlantic nights. Those features remain today, reminders of a new kind of devotion – not to God, but to guiding ships through one of the most dangerous coastlines in Europe.

20th Century: Preservation and Recognition

By the 20th century, Skellig Michael was no longer just a relic of faith or a working lighthouse station. Scholars, historians, and conservationists began to recognise its extraordinary cultural value – a place where history, archaeology, and the raw Atlantic landscape were fused.

The culmination came in 1996, when UNESCO inscribed Skellig Michael as a World Heritage Site. The designation praised it as a “unique example of early Christian monasticism deliberately sited on a pyramidal rock in the ocean.” Its survival across more than a millennium – from monks and pilgrims to lighthouse keepers and surveyors – marked it as a site of outstanding universal value.

Universal Value Recognised by UNESCO

When UNESCO inscribed Skellig Michael in 1996, they leaned heavily on the ICOMOS evaluation, which praised the site not just for its beauty and isolation, but for what it represents in human history.

- At the Edge of the World: Skellig Michael symbolises the spread of Christianity and literacy far beyond the old boundaries of the Roman Empire, all the way to Ireland’s storm-lashed Atlantic outposts.

- A “Desert in the Ocean”: ICOMOS described it as the ideal small monastery, a wilderness counterpart to the desert retreats of early Christian monks in Egypt and the Near East.

- Exceptional Preservation: Unlike many medieval monasteries, Skellig was never heavily plundered. Its huts, oratories, and terraces remain some of the best preserved monastic remains on any Atlantic islet.

- Part of a Golden Age: The ruins are not isolated relics. They connect directly to the wider “Celtic golden age,” when Irish monks carried Christianity and learning across Europe, to France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and beyond.

- A Story of Migration: In this way, Skellig Michael is also a reminder that migration is not new. It is a constant of the human condition, whether monks seeking God in exile or entire cultures moving across borders.

For UNESCO, this was not just an Irish site, but a place of universal significance — a stone witness to faith, learning, and endurance at the edge of the known world.

21st Century: Modern Fame

In 2014, Skellig Michael stepped into a different kind of mythology. Chosen as a filming location for Star Wars: The Force Awakens and later The Last Jedi, the island became the screen home of Luke Skywalker’s retreat. Its ancient stone steps – once climbed by monks in prayer – now carried Rey in her search for the last Jedi.

The decision to film here was daring. Access is difficult, the weather unforgiving, yet the island’s otherworldly beauty needed no special effects. What had once been a remote monastic outpost suddenly became one of cinema’s most iconic landscapes.

If reading about the Skelligs has stirred your curiosity, the best way to truly understand them is to experience them from the water with AquaTerra. Whether you choose to circle these extraordinary islands on our Skellig Coast Round Tour or take the unforgettable steps onto Skellig Michael itself with our landing experience, your journey begins in Valentia Island. Visit our Book Now page to explore dates, availability and choose the Skellig adventure that’s right for you.